Keeping mum?

A few people have contacted us, concerned that the free availability of indexes to births compromises their identity security.

The widespread use of mothers’ maiden names and dates of birth as passwords (NOT security checks) worries us, too. The problem isn’t particularly that this data is widely available, from numerous sources, the problem is that it is relied upon as a form of password, usually on multiple sites. Long story short: if you have used your mother’s maiden name as a password, or a place name as a password, please CHANGE IT NOW.

Unfortunately, there used to be a reliance on easy to remember passwords (aka "security questions") such as 'mother's maiden name' and 'place of birth'. This is a dangerous practice, and is not recommended by the government: https://www.cyberaware.gov.uk/passwords. However, despite advice from the Home Office, some companies continue to use them. If one website is hacked, that data becomes associated with your email address and potentially other passwords or personal data. We therefore advise people not to use websites that ask for such information as passwords, and if they still wish to use the website, to use real passwords instead (no one is going to be checking up that DeputyDawg is not your mother’s maiden name / place of birth, except in some very special circumstances), but a strong password, as described in the above link and to use different passwords on each site used.

If you struggle to remember the dozens of passwords you already have (and the additional dozens created when you change good-old-mum to a number of strong passwords is going to result in a lot more forgotten passwords)there are now a number of password management tools/devices which you could look into. For example, many browsers have a simple tool. However you need to be careful that if they share the passwords with your phone, tablet, or other device that might get stolen or mislaid, that it is protected with a master password or security number (not your year of birth). Alternatively, you can use an online password vault or safe (you just have to remember one password). For added protection, you can encrypt the document you store the passwords in, too.

Using mother’s maiden name or place of birth in essence creates the same password on multiple websites, (and the fact that it is being used shows they are websites run by companies with little regard for data security), but this is not the only problem: these are both easily found.

Sometimes, when you’re asked to give your date of birth, this is a legitimate check as to who you are and/or how old you are. For example, if you have an interest in alcoholic drinks and visit a website that promotes one, you may be required to declare that you are legally old enough to drink in your country, and provide your date of birth. I personally feel that it's fine to answer that you were born on 5 June 1952 when in fact you were born on the 5 February 1955 in these circumstances. Sometimes it is used to check that you are you, not another Jo Smith - for example at every stage during a medical procedure where one patient can get substituted with another by accident. This seems to me to be reasonable - the identification does need to be something that will be memorable without recourse to a computer, and memorable when one is perhaps very ill and confused.

Rarely are dates/places of birth, or mothers’ maiden names truly used for security purposes (as opposed to as pseudo-passwords). The last time I can remember being asked for genealogical data was on an application for a visa for India a couple of years ago. The Index information on FreeBMD and in other search engines which can be searched for a fee (or for free in many libraries) is actually not very useful on its own for answering such questions - one of my grandmothers, for example, was born in a small Northamptonshire village - and that is the answer I (correctly) put on the form. But the place name in the index is not the birth town/village: it is the Registration District for that place - which can even be a location in the next county. While more recent registrations contain the full date of birth, most are only identified by quarter of registration. Since the parents have 42 days to register a birth, it is not uncommon for the birth to be registered in the following quarter. So FreeBMD was no help for filling in the visa application in this area either.

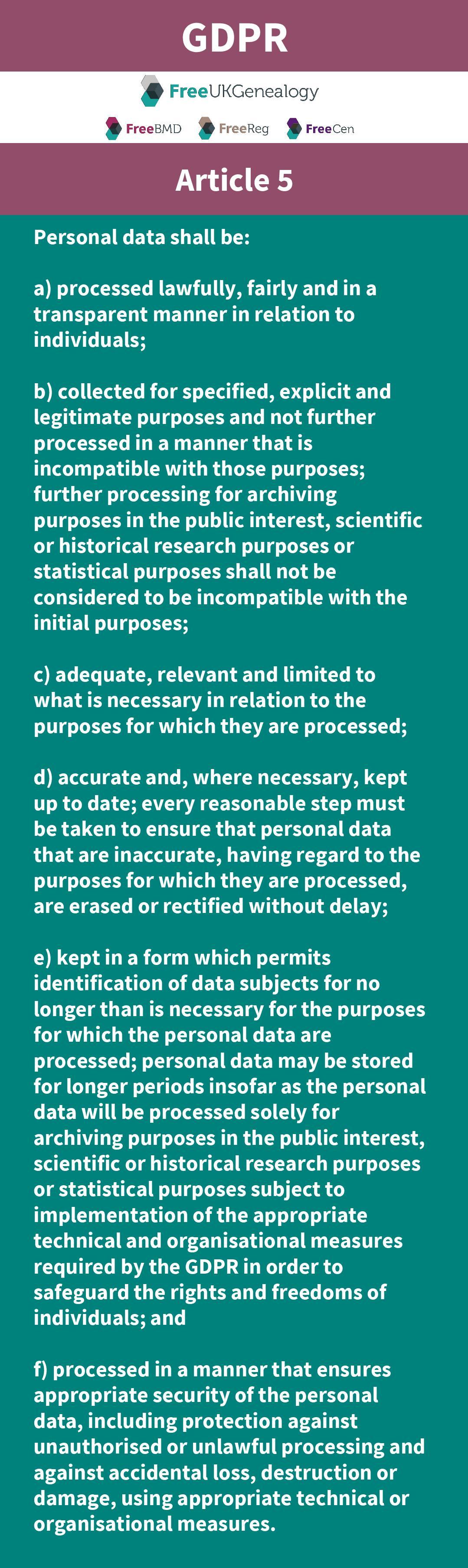

I would like to reassure you that the data we show to the public is not behind a sign-in or paywall, and we intend to keep it this way because it is public data, which we make freely available to achieve our aims as a charity. Those who give us permission to transcribe are free to put restrictions on access to the index and transcriptions, which we always honour by not showing the data until the date specified / time elapsed required. For FreeBMD, this permission is given by the Government.

Liability disclaimer: The above advice is based upon that given in https://www.cyberaware.gov.uk/, and you should check this or similar resources. We have not investigated the advice given by this website, and you should not rely on the information as we have presented it here and can take no responsibility for any loss that results.